Maybe this is why I’ve focused on reportage and my personal observations rather than fiction:

Readers have become so canny about the way fiction works, so much has been written about it, that any intense work about sexuality, say, or race relations, will be understood willy-nilly as the writer-s reconstituting his or her personal involvement with the matter. Not that people are so crass as to imagine you are writing straight autobiography. But they have studied enough literature to figure out the processes that are at work. In fact, reflecting on the disguising effects of a story, on the way a certain set of preoccupations has been shifted from reality to fiction, has become, partly thanks to literary criticism and popular psychology, one of the main pleasures of reading certain authors. What kind of person exactly is Philip Roth, Martin Amis, Margaret Atwood, and how do the differences between their latest and previous books suggest that their personal concerns have changed? In short, the protection of fiction isn’t really there anymore, even for those who seek it.

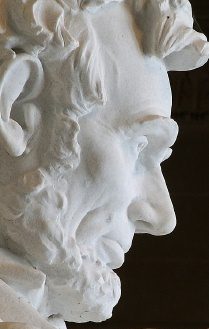

And this comment from the Dish reflects something I feel is especially true about our times when people upload every aspect of their behavior to the Internet for everyone else to see. Today’s biographies no longer hide the warts and blemishes of the great and mundane people who’s lives they chronicle. Its often unsettling, frequently disappointing but ultimately liberating. My heroes (and some villains) were humans not saints or even pure evil. They had clay feet like me and yet they managed to transcend and enrich the world or diminish it with great abandon:

Far more interesting and exciting to confront the whole conundrum of living and telling head on, in the very different world we find ourselves in now, where more or less anything can be told without shame. Whether this makes for better books or simply different books is a question writers and readers will decide for themselves.