Five years ago I began but quickly shelved an argument with the attorney I was working with who helped Let Duluth Vote challenge the Red Plan in Duluth. I told him that the law was tempered with politics. He strongly denied this, so much so I thought it useless to argue. But its true. Judges bring their political thinking and loyalties into their job just like they bring their other experiences and family connections. Many of them have to run for their offices. As is said of politicians: those who do not get elected cannot legislate, so to with judges; those who can not get elected cannot judge.

It is wishful thinking to expect all or even most judges to be blindly blind to the world around them and simply rule on the basis of sometimes out-dated or ill-worded laws when the public can throw bombs at them for doing so. Judges in India and Pakistan probably get year round police protection when they make unpopular rulings like the recent Indian Court that opened an Indian Temple recently to women of an age to menstruate.

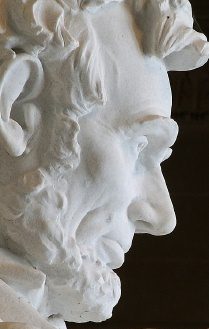

With this prologue let me introduce the first four paragraphs of an Atlantic article on our Supreme Court’s Chief Justice John Roberts. They contain almost exactly my thinking about him. I’ve read no further than this for now but here’s the article in full and here below are those first four paragraphs: (This article appears in the March 2019 issue.)

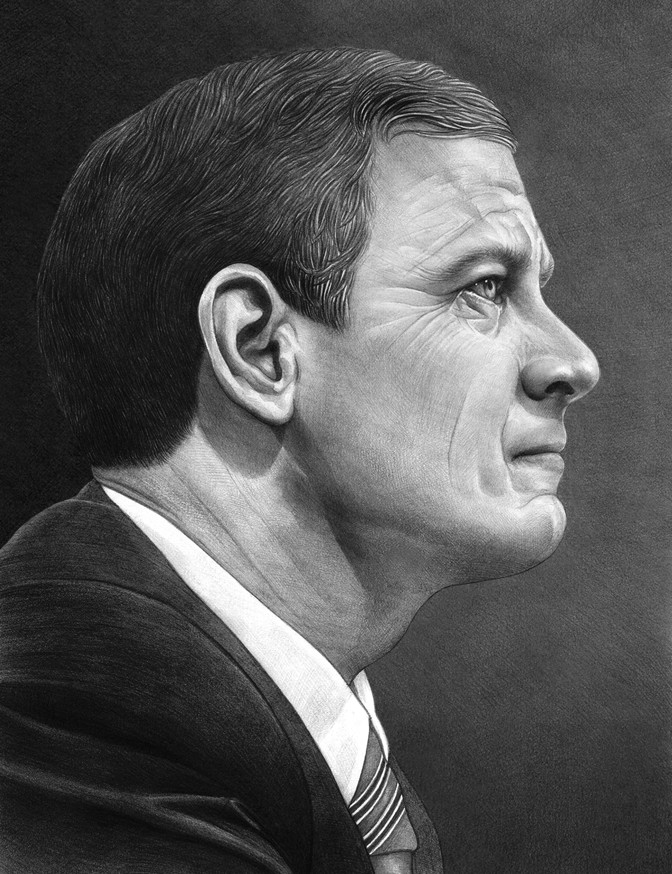

Two years ago, Chief Justice John Roberts gave the commencement address at the Cardigan Mountain School, in New Hampshire. The ninth-grade graduates of the all-boys school included his son, Jack. Parting with custom, Roberts declined to wish the boys luck. Instead he said that, from time to time, “I hope you will be treated unfairly, so that you will come to know the value of justice.” He went on, “I hope you’ll be ignored, so you know the importance of listening to others.” He urged the boys to “understand that your success is not completely deserved, and that the failure of others is not completely deserved, either.” And in the speech’s most topical passage, he reminded them that, while they were good boys, “you are also privileged young men. And if you weren’t privileged when you came here, you’re privileged now because you have been here. My advice is: Don’t act like it.”

As Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s maudlin screams fade with the other dramas of 2018, Roberts’s message reveals a contrast between the two jurists. Whatever their conservative affinities and matching pedigrees, they diverge in temperament. The lingering images from Kavanaugh’s Senate confirmation hearing are of an entitled frat boy howling as his inheritance seemed to slip away. By contrast, Roberts takes care to talk the talk of humility, admonishing the next generation of private-school lordlings not to smirk.

The chief justice also carries himself in a manner that reflects his advice. He chooses his words carefully. He speaks in a measured cadence that matches his neatly parted hair and handsome smile. He is deliberate and calm, not just in his public remarks but in his work as a judge—and as a partisan. Roberts declines to raise his voice or lose focus, because he understands politics as a complex game of strategy measured in generations rather than years. He also recognizes, but will never admit, that although politics is not the same thing as law, the two blend together like water and sand. More than 13 years into his tenure as chief justice, Roberts remains a serious man and a person of brilliance who struggles, under increasing criticism from all sides, to balance his loyalty to an institution with his commitment to an ideology.

The first biography of Roberts has arrived, Joan Biskupic’s The Chief. It will not be the last. A well-reported book, it sheds new light but is premature by decades. (Biskupic is a legal analyst for CNN.) As our attention spans dwindle to each frantic day’s headlines, we can forget that the position of chief justice is one of long-term consequence. Only 17 men have filled that role, and they have presided over moments of national crisis, shaping our government’s founding structure (John Marshall), hastening its civil war (Roger Taney), responding to the Great Depression (Charles Evans Hughes), and enabling the civil-rights revolution (Earl Warren).

Roberts seems ever likelier to face an equally daunting test: confronting a president over the value of the law itself. A staunch conservative, he has broken ranks with the right in a major way just once as chief justice, by casting the deciding vote to save the Affordable Care Act in 2012. What will Roberts do if the clerk calls some form of the case Mueller v. Trump, raising a grave matter of first principles, such as presidential indictment and self-pardon? He portrays himself as an institutionalist, but we do not yet know to what extent this is true. He must necessarily prove himself on a case-by-case basis, which injects a note of drama into his movements. Roberts is the most interesting judicial conservative in living memory because he is both ideologically outspoken and willing to break with ideology in a moment of great political consequence. His response to the constitutional crisis that awaits will define not just his legacy, but the Supreme Court’s as well.